Asset owners are increasingly questioning the accuracy of private asset valuations on their books, amid a growing dispersion between the performance of publicly listed assets on the one hand, and private assets on the other.

The figures tell a clear story. While rising inflation, a dramatic shift in central bank monetary policy and an increasing probability of recession over the course of 2022 caused the S&P/ ASX 200 A-REIT Accumulation Index to be down 20.6 per cent by 31 December 2022, private property managers bucked the trend, with the unlisted MSCI/Mercer Australia Core Wholesale Monthly Property Fund Index up 6.4 per cent by year end (see chart below).

“I’d be very interested to understand exactly why returns in this sector have been so outsized compared to everything else,” one investment risk manager told Fund Business.

“Are there fundamental reasons other than perhaps the illiquidity premium which could justify that level of outperformance, or are our private asset valuations about to collapse in a big fat heap as valuations catch up?”

It’s a question that is commonly asked in conversations about themes that keep investment risk managers awake at present.

The lag in valuations goes some way towards explaining the difference in performance numbers. Private assets are valued at three-to-six month intervals, often referencing comparable transactions. In a market downturn, such transactions are fewer and farther between, causing valuations to remain artificially high and volatility to remain muted, or so the argument commonly goes.

Listed vs unlisted property: a case in point

Take the case of the above-mentioned A-Reits and private property portfolios for example, which are both portfolios with similar types of properties as underlying assets.

While the S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT Accumulation Index returns have experienced significant volatility over the past decade, the unlisted MSCI/Mercer Australia Core Wholesale Monthly Property Fund index returns have proven remarkably stable. Those swings that have occurred have lagged the steep peaks and troughs of the A-REIT market.

By that logic, the unlisted property sector could be due for a significant correction which may not yet be priced in.

However, while the valuation lag is a factor, it may not be as straightforward as often suggested.

For one, this argument assumes that public markets are closer to true value when, in reality, share prices are often not aligned with intrinsic value either, particularly in times of material uncertainty.

For another, external valuers also take into consideration macro assumptions, pipeline transactions and conversations with brokers, as well as detailed discounted cashflow analyses (DCFs) when valuing unlisted assets. Hence, the absence of a movement in valuations may not necessarily mean the price is stale.

The lag in revaluations is also not the only driver explaining the return differential. The underlying assets may be very similar, but REITs and unlisted property funds are very different investment vehicles, that are priced differently and that have different risk/return characteristics.

Comparing the two like for like – as proposed in the early days of the YFYS performance test – would be quite misleading.

“In unlisted markets, valuations are determined at the property level by looking at comparable sales. Listed A-REITs trade on an exchange and the prices of those securities are determined by investor sentiment and prevailing equity market conditions. The valuation mechanism in REITs is completely different to the way that unlisted vehicles are valued and, as shown below, these prices can significantly deviate from the underlying value of their portfolios. This is why you are seeing a deviation in their returns,” Damien Damiano, Senior Manager, Performance & Investor Reporting at ISPT told Fund Business.

Damiano said it’s the same story when comparing risk and returns. “If listed and unlisted property indices were comparable, you’d expect to see similar risk/return characteristics, but that’s not the case. Over time, unlisted property funds exhibit stable returns with lower variability compared to listed property funds, which have higher levels of risk. If anything, A-REITs and the equity markets have a stronger relationship over the longer term, particularly in down markets, when they appear highly correlated to listed equities.”

Beyond the more obvious differences in valuation timing and pricing mechanisms, there are other differences too that could explain performance differentials in a more nuanced fashion. That includes differences in the use of leverage, the illiquidity premium for unlisted investments – most observers agree that investors should be compensated for giving up liquidity – and possible control, size and complexity premia for certain unlisted investments.

Indeed, one asset owner told Fund Business that the impact of control is often more significant than the liquidity premium where valuation differentials between listed and unlisted investments are concerned. While listed company shares only give the investor a small percentage of interest in the company, unlisted investments are typically valued on a control basis given that most investors would own larger percentages – for property often in excess of 50 per cent. For the same reason, listed company take-overs are typically valued at a premium to the traded price.

The question remains whether those factors are significant enough to justify the 20% performance differential that’s currently on the books.

Infrastructure in focus

In the infrastructure sector, similar questions exist around the reasons why unlisted returns have been higher than listed, with some questioning the sustainability of these excess returns.

A recent report by Maple Brown Abbott, found that for the 10 years to 31 December 2022, the listed infrastructure sector delivered 9.5% p.a. while the unlisted infrastructure sector delivered 11.4% p.a. (see figure below).

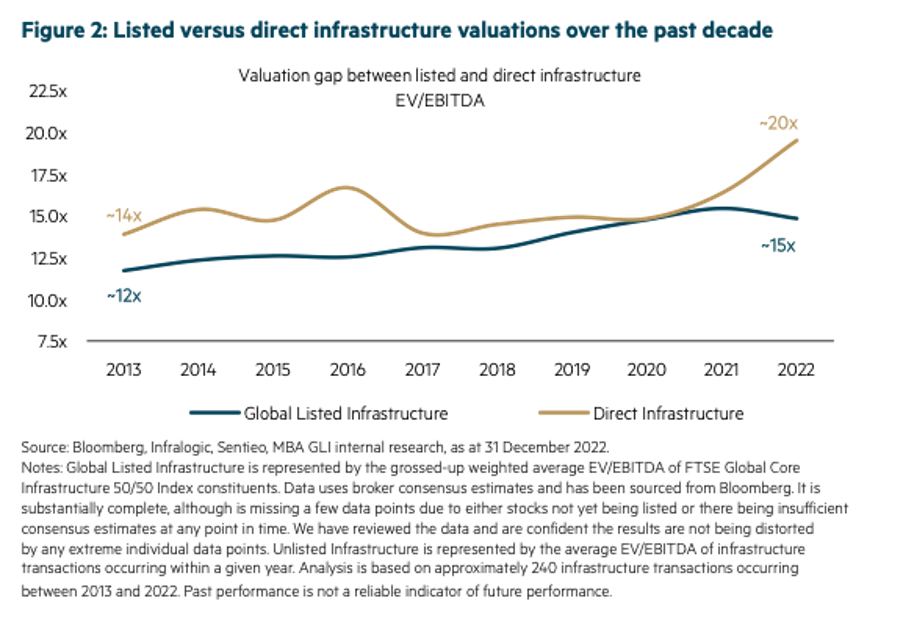

However, over the course of the past two years, there appears to have been a noticeable increase in the valuation gap, measured as the Enterprise multiple (EV-to-EBITDA), between listed and direct infrastructure valuations (see figure below).

There are of course some differences between the composition of the two indices. The EDHEC index is an equal weights index, which would give small infrastructure projects with high development returns the same weighting as a large stable infrastructure investment with lower returns, while the FTSE index is weighted based on market cap and would hence give higher weightings to larger, more stable companies. However, those factors aside, infrastructure assets in listed and unlisted markets under review are otherwise broadly equivalent, based on the same regulatory and legal constructs, with no discernible difference in management expertise.

In fact, a different study conducted by Maple-Brown Abbott that analysed listed versus unlisted infrastructure through the lens of UK water utilities, found that listed water utilities in the UK actually demonstrated superior operational performance and returns to equity compared to their unlisted counterparts.

According to Andrew Maple-Brown, co-founder and managing director at Maple-Brown Abbott Global Listed Infrastructure, the reason why unlisted infrastructure has traditionally outperformed listed infrastructure has been due to materially higher debt levels used in unlisted assets, which has benefitted them in a period of rising asset prices, and where the valuation gap between listed and unlisted assets has widened. Over the course of the past two years, a lack of supply coupled with significant ‘dry powder’ on the part of asset owners has caused the valuation gap to increase dramatically.

“A key contributor, in my opinion, is simply the weight of money. There is so much money being pushed into the private sector with a limited supply of assets which is creating a lot of tension within auction markets,” Maple-Brown told Fund Business.

Indeed, there is a perception that infrastructure is a relatively safe asset, providing consistent inflation-linked returns at low volatility and a welcome source of diversification, making it a particularly attractive investment for large asset owners able to optimise debt levels and therefore the leverage effect.

That perception of safety is likely to continue to hold, making infrastructure investments an attractive diversifier at a time when all other markets are under significant pressure.

“In terms of the outlook I would argue it is still a good environment to own infrastructure. We believe that inflation is still high, we think we are in a relatively low growth environment, and we think infrastructure can provide long-dated, stable cashflows with inflation linkage and portfolio diversification benefits. We think all those characteristics will continue to be important for investors,” Maple-Brown said.

That’s the case for both unlisted infrastructure assets, as well as listed assets, but with one caveat: on paper at least, unlisted infrastructure is likely to face some significantly stronger headwinds than its listed counterpart, causing Maple-Brown to suggest the tide may be turning. He said the higher prices currently paid in direct markets will likely lead to a significantly lower ongoing earnings yield over time.

“Even if valuations between the listed and unlisted market remain at the current wide range (and returns for investors are driven solely by current earnings and earnings growth as opposed to multiple expansion), then listed infrastructure should produce higher returns than unlisted infrastructure, simply due to the very different earnings yields currently available to investors,” Maple-Brown said.

“For unlisted infrastructure to overcome this headwind and produce equivalent or better performance than listed – when investing in effectively the same assets, we’d need to see

valuations of all assets continue to rise, so their higher leverage is rewarded; and/or the gap between listed and direct infrastructure valuations continuing to widen,” he said.

“If either of these assumptions begins to reverse, then we would expect unlisted infrastructure returns to face greater performance headwinds relative to listed.”

Unlisted asset valuations will be discussed in more detail at the Private Markets Summit in Sydney on May 18th; along with implications for risk management and asset allocation at the total portfolio level; performance measurement and attribution considerations; investment governance; due diligence; data management and operations among other topics.

For more information, visit https://www.fundbusiness.com.au/private-markets-summit/